There are a number of communication tools that can be used to communicate monitoring findings and recommendations. Monitoring reports are the most common type of tool, but this section also covers other types of reporting tools.

Monitoring Reports

Monitoring reports are usually period reports that organizations make public on an annual, biannual, or even monthly basis. These reports should include certain key sections: introduction, methodology, findings, conclusions and recommendations.

In the introduction, the report outlines the reason for this type of monitoring, the importance of the target political process, who is responsible for the process, and the importance of improving the process. The methodology section is where you explain the monitoring approach, what tools you used, and what activities you carried out.

The findings section should report the information you produce through your monitoring and your data. This is the evidence that shows what is happening to a political process. Infographics that tell a story and portray your information in an easy-to-understand format are included in the findings sections.

The conclusion section includes your analysis of why you think something is happening or not happening. This is where you evaluate the causes for the gaps or deficits in the target political process and the root causes of government inaction to change the issue, such as lack of will, know-how or capacity.

The recommendation section details the recommendations that were developed based on your analysis of the evidence. This section provides specific proposals for improving the target political process and serves as a call to action for the target government institution. Every recommendation in the monitoring report should abide by five rules, also known as the LEADS rules.

Each recommendation should be:

- Linked to the findings. It is not the time to bring up new issues that were not foreshadowed in the findings section.

- Evidenced well in the report.

- Addressed to a specific institution to be clear about who the call to action is for.

- Doable — they should be within the power and capacities of the target institutions.

- Short — not too general but not too long as to be confusing.

For example, if you’re recommending that an institution be more transparent, simply stating that “the institution should be more transparent” is too short and too general. Transparency is a broad term, and as such, a recommendation is more effective if it is concise but specific to the target institution and describes the desired standard or how to improve the process. However, you should avoid going into too much detail so as not to overwhelm the audience. Additional details can be included in the findings section.

A Monitoring Report checklist can be found in the Annex to assist you in writing an effective monitoring report.

Parliamentary Monitoring Reports

The most common products coming out of parliamentary monitoring initiatives are monitoring reports, although as the internet expands, more of the reporting is moving online through websites and scorecards. Groups have published parliamentary monitoring reports either annually or after each legislative session. The reports are generally written for MPs or local governments, donors and the media, but can also be distributed to the public. Depending on the purpose of the monitoring (openness, functionality or MP performance), the reports can contain recommendations on any or all of the following topics:

- Fulfilling legislative standards requirements;

- Enhancing capacities to draft and approve legislation;

- Organizing public hearings as part of the legislative development process;

- Capturing and acting on citizen priorities;

- Implementing legislation; and

- Making budget procedures transparent.

Performance Scorecards

Another reporting tool used to raise awareness and communicate findings is the performance scorecard. Groups typically publish legislative scorecards primarily for the benefit of citizens and other CSOs. Scorecards can be written in a narrative form or in a more heavily statistical scorecard format. The types of information revealed in legislative scorecards are much more focused on the “nuts and bolts” of legislative procedures than the recommendations laid out in monitoring reports, and have included information on:

- Legislator attendance in plenary and committee meetings;

- Participation in CSO roundtables and debates;

- The number of laws debated; and

- The number of meetings with stakeholders initiated by legislators.

Websites and Social Media Pages

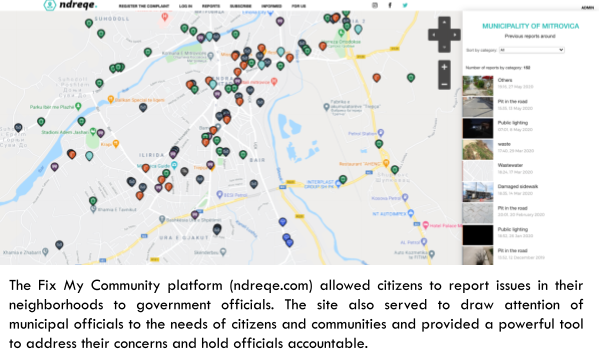

Websites can be powerful tools for raising awareness of the monitoring initiative’s findings and recommendations. Moreover, software tools that can process, analyze and visualize parliamentary data, known as “parliamentary informatics,” can be integrated into websites. Websites can also be used to hold legislators accountable and increase interaction between legislators and their constituents. The findings and analyses on monitoring websites can provide citizens with the information they need to begin advocacy or organizing campaigns, or simply allow them to make more informed decisions about how they will vote in coming elections. Monitoring websites can also contain contact information for legislators, which can improve access for citizens. More recently, websites and social media pages have been used to facilitate questions and answers between legislators and citizens on matters discussed in parliamentary proceedings.

Examples of the kind of information included on monitoring websites include:

- Consistently updated parliamentary developments;

- Monitoring reports;

- Background documents on parliament, parliamentary blocs and committees;

- Parliamentary news and studies;

- Articles and brief analyses of monitoring data written by partners’ observers and researchers;

- Comments posted by citizens on social media;

- Citizen questions and MP responses;

- MP bios; and

- MP contact information.

Contact Relationship Management Systems

In addition to websites, awareness-raising and communications campaigns can also benefit from Contact Relationship Management (CRM) systems that allow you to more efficiently and effectively share information with the public. These tools enable you to keep a contact database of stakeholders and manage systematic communications with select contacts over time. For example, a CRM tool can be used to share monitoring reports and information with a group of interested stakeholders, identify key audiences based on their interests or actions, or even organize events or campaigns. NDI is a contributor to CiviCRM,46 the premier open-source CRM platform, which it provides for free to NDI staff and partners through its DemCloud hosting service.47

Infographics

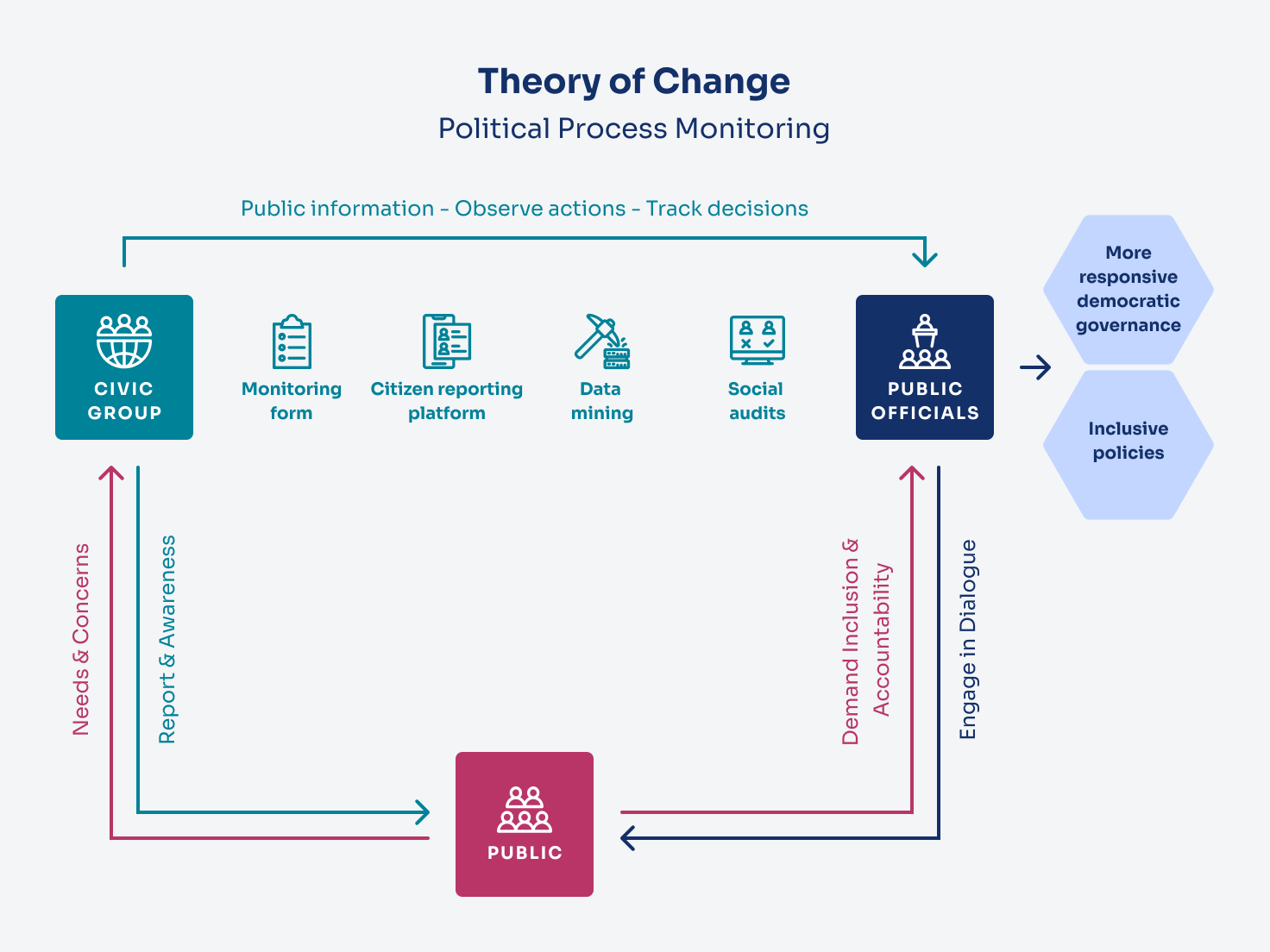

Infographics, as the word implies, report info (information) through graphics. They tell a story in a visual and easy-to-understand manner and can help simplify complex data by “connecting the dots.” They can be used to concisely explain the target political process, who is responsible, and what the issues or gaps are.

Some creativity and technical skills are required to create infographics. However, there are plenty of resources to help you visualize your data that don’t require you to be an experienced visual designer, such as Infogram or Canva.48 These sites have various templates to help you get started and basic free versions that have some limitations but are sufficient for simple illustrations.

There are six steps to making an effective infographic: 1) identify the message you want to send; 2) select a template; 3) import your data; 4) add your message; 5) refine and simplify your message; and 6) test your messaging. If the message and graphic makes sense and are easily understandable to someone unaffiliated with your monitoring initiative, then it is probably ready to be disseminated.

Consistent branding can help improve the credibility of your infographics and ensure that they are accurately attributed to your organization if shared out of context online. This can be done by including your group’s logo, using colors consistently, or including a hashtag or hyperlink that leads back to more information about your monitoring initiative.

Town Hall Meetings

The data gathered through the monitoring initiative can also be used to inform town hall meetings, roundtables, or debates attended by a combination of legislators, CSO representatives, citizens, and political party members. Monitoring groups and grassroots CSOs have organized these types of events within their networks to provide an opportunity for citizens to directly and constructively engage with their representatives. Discussions and debates typically revolve around legislative roles and performance, citizen perceptions of legislators, and topics identified as problem issues in the monitoring findings. These public forums also provide an opportunity for you to explain the importance of the monitoring initiative, disseminate monitoring reports and other reporting products, and gather ideas for how to enhance future monitoring initiatives. These public forums have the potential to inspire citizens to use the monitoring findings to inform advocacy campaigns and other organizing and awareness-raising initiatives.

Hybrid or virtual town hall meetings can leverage technology to increase the reach of these activities. Through video conferencing tools like Zoom or Signal,49 citizens can be empowered to engage with representatives even if they cannot be physically in the room. Broadcasting and recording in-person town hall meetings can have a positive effect on transparency for both journalists and members of the public who are interested in the proceedings but might have barriers that limit their ability to engage in person. Telephone town halls, which use teleconferencing software to actively invite citizens to audio-only forums, can further increase access for people who might not have internet connections or computers capable of participating in Zoom conferences. This format of town hall can be particularly effective at reaching aging populations.