Obviously, integrating an information technology tool was more work in the beginning, and it did have a cost. D+ had to decide how to design the online tracking website, the branding, the name of the website, and everything that goes into making a user-friendly website. It was challenging to design something that listed everything D+ was monitoring and tracking, and yet still have a site that was easy to navigate. However, this made the job of monitoring much easier down the road: D+ did not have to worry about producing monthly or periodic monitoring reports or about coordinating monitoring tools with NDI.

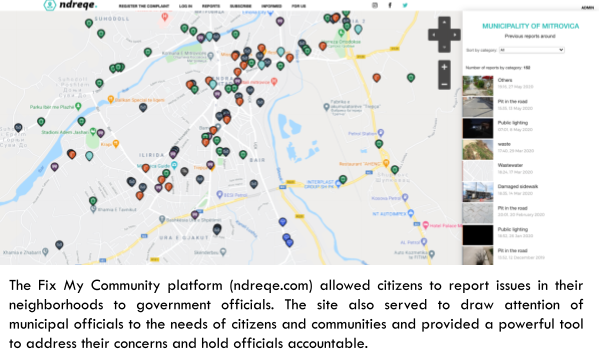

The Fix My Community platform (ndreqe.com) was adopted from open-source software offered to organizations by NDI. However, D+ wanted to customize it for Kosovo users by putting in an interface and cutting out a few steps for reporting. It turned out to be a larger, and longer, task than initially thought for adopting software that had already been developed. However, the app’s usability was drastically improved, and it was worth the extra hours when it came time to promote the website to communities and municipalities.

Evaluating Impact

The first impact of this campaign monitoring was that political parties began articulating their election promises better. The second, and more important, development was that parties in the government began paying more attention to their campaign programs. Third, citizens and the media had a tool to keep the government more accountable for their election campaigns. Social accountability in government was strengthened as citizens began taking on the role of watchdog directly.

Additionally, in the next election campaign, D+ noted that political parties were more careful and realistic about their promises and their platforms. This monitoring initiative generated more accountability and responsiveness by the government. It also generated more citizen participation in government affairs, as the people had the information about parties’ promises and their follow-through at the tips of their fingers.

The impact of the Fix My Community53 website ndreqe.com increasingly turned the attention of municipal officials to the needs of citizens and communities and provided a powerful tool to address their concerns and hold officials accountable. The website also became a useful tool for planning and identifying larger issues in neighborhoods, as citizen reports pinned on the municipality map pointed clearly to larger problems with waste management, degrading roads and damages to infrastructure.

Lessons Learned

Democracy Plus activists pointed out several lessons they learned during and after the monitoring process.

Invest time and effort at the beginning of the monitoring initiative to repeatedly stress the scope of the monitoring, what exactly the organization is monitoring and the objectives.

Manage media, citizen and politician expectations about the monitoring efforts. At times journalists asked why D+ was pushing politicians to move forward certain projects that some sections of society opposed. D+ had to explain the methodology and the monitoring objective of keeping politicians accountable to their campaign promises, rather than advocating certain projects.

Similarly, politicians questioned monitoring as being subjective because D+ monitored only a few of the campaign promises. D+ had to regularly explain that only “concrete and measurable” projects were being monitored precisely to be objective in their monitoring.

Create separate social media pages for the organization and the monitoring initiative to maintain focus on the initiative. D+, as a watchdog organization, had separate teams monitoring different political processes. Social media was an important communications tool. However, using the organization’s own social media pages often made it difficult to keep the audience’s focus on specific monitoring initiatives, and forced the organization to prioritize the different initiatives’ messages on social media or risk overwhelming the audience. Using separate social media pages for the different monitoring initiatives overcame these issues. Once D+ created separate pages for ndreqe.com, it began attracting citizens more interested in local governance issues, which was the focus of that monitoring initiative.

Invest in reaching citizens in their own communities to make them a part of the monitoring efforts, as well as inform and educate them better about the political processes you are monitoring. Ultimately, change and improvements in a political process occur if there is pressure from constituencies. While D+ made efforts to go into various locations across Kosovo to educate people about the importance of keeping politicians accountable and transparent and inform them about using their monitoring platforms, it was assessed as crucial that this should have been done more often and more broadly.

Democracy Plus began to put most of these lessons in practice over the course of their monitoring. The resulting impact demonstrates that monitoring is a continuous course of action for lasting change.